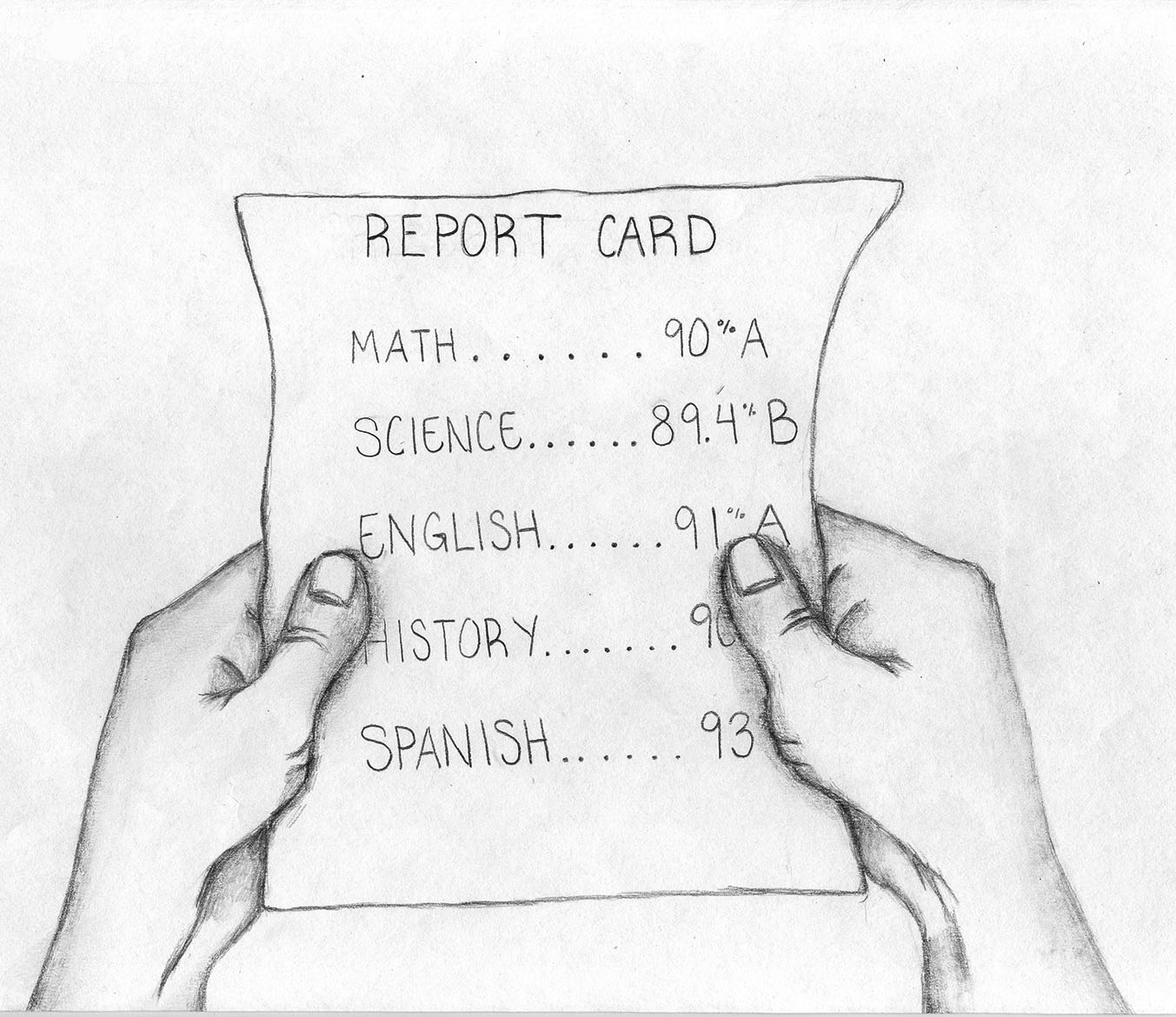

For a high school student, there is nothing more terrifying than an 89.4 percent.

A tricky calculus ensues: does the student ask his or her teacher to round the grade? Will the teacher round the grade automatically? Has the student invested so little effort in the class that his or her request is sure to be rejected?

The stress begins to accumulate as one is doused in uncertainty, the anxiety of the rounding game inducing paranoia about the next potential move. But when the final grade is posted, the apprehension recedes, only to make way for a powerful, yet unjustifiable rage.

Because that student has earned a B.

Having concluded the first semester, the sighs about failed final exam goals and the complaints about teachers who didn’t round grades are blooming. In almost any class, you are sure to find someone who has been “unfairly treated” by his or her teacher, such claims reliant on the fact that the student was not given an A, despite failing to earn one.

There seems to be a sense of entitlement among students, an opinion that performing “well enough” in a class means performing excellently. Many have forgotten that the grade categories exist for a reason, filtering and rewarding students based on their academic accomplishments. To be blunt, an 89.4 percent is not an A. It is a B, a B as clear as the black ink that designates an 80 percent to an 89.99 percent as “above average.” A’s are not supposed to be easy to earn. Not everyone can be academically superior. When students complain about not being given the higher grade, their complaints only illustrate the rationale for not rounding: the grade is given, rather than earned.

The consensus that an 89.5 percent or higher is an A is absurd enough — to extend the range of excellence even more not only gives students the illusion that they are elite, but disincentivizes the hard work that is necessary to actually earn a superior grade. Teachers are not rewarding students’ motivation when they round grades — they are siphoning it away, lowering the threshold for what is considered excellent, conveying that students can exert less effort and still earn the same reward.

The impact extends beyond school, though. Students who are being inappropriately rewarded are also being deceived, trained in a manner that will encourage them to just be “good enough.” In the future, when seeking employment or pursuing higher education, these students will be disadvantaged by the mediocrity they have internalized. The reality is that extraordinary determination is a prerequisite to self-advancement. You can’t climb the ladder of prestige if you are in the middle of the pack.

While school is not a competitive job market, our out-of-school lives will be. As adults, we need to be prepared, cognizant that those who do not earn profits are not given them regardless. Perhaps grades should be earned in the same way.