Nomophobia: a technological illness you may not know you have

Every summer for the past seven years, senior Lindsay Malkin faced the prospect of parting with her phone for two months as she left for overnight camp. When she sat on the six-hour bus ride to camp, she felt like she was missing something.

Every summer for the past seven years, senior Lindsay Malkin faced the prospect of parting with her phone for two months as she left for overnight camp. When she sat on the six-hour bus ride to camp, she felt like she was missing something.

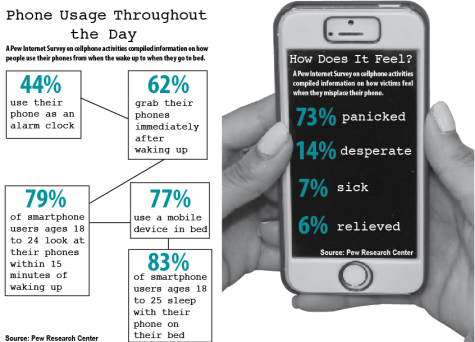

Attachment to a cellular device like Malkin experienced has become so prevalent among teenagers that it has been given its own term, “nomophobia,” short for “no-mobile-phone-phobia,” according to stress reduction expert Melissa Heisler. Although it is not an official diagnostic category for psychological experts, Heisler said it refers to the desire that some people experience to have their phones with them or near them all the time.

“To me, nomophobia is defined by a connection to our technology above all else, above caring for ourselves, above human connection,” Heisler said.

This obsession with technology among adolescents is growing at an alarming rate, according to Heisler. Because previous generations grew up without technology that permitted constant connectivity, they learned to be patient and entertain themselves while offline. The current generation, Generation Z, has been born into a different “world of communication.”

“From an early age, technology has allowed [the current generation] to have instant connectivity,” said Heisler. “Waiting and patience are no longer learned.”

Malkin said she experiences a mild form of nomophobia, as she feels she almost always wants to have her phone with her.

“I always have it with me unless I forget it, but I never forget it,” she said.

Heisler attributes nomophobic behavior to psychological and biological addiction and the desire for immediate gratification.

“Every time we answer a text, tweet a response and like a post, we are filled with feel-good endorphins,” said Heisler. “The faster we answer [and] the more times we connect, the more endorphins.”

John Suler, professor of psychology at Rider University, said nomophobia is the result of aiming to avoid isolation.

“Especially with the advent of mobile devices, people seek out constant connection,” said Suler. “They never have to be alone, separated from significant others and mother-internet herself.”

Malkin said she experiences this instant gratification by staying connected.

“I like knowing what’s happening,” she said. “If I feel out of the loop, it’s weird. … If there are plans being made or something like that and I’m not part of it, I feel left out.”

Suler said that when he discusses nomophobia with his students, he leads a guided imagery exercise in which the students envision how ties to technology impact their lives. One student saw himself with his phone glued to his hands.

“[Another] student saw herself as part of ‘the cloud,’ sensing that her whole life was there, uploaded, never to be taken back,” Suler said.

Heisler said there are many negative consequences of nomophobia, such as anxiety from waiting, franticness from a sense of urgency, life imbalances that separate people from friends and family, and insomnia and exhaustion from unrealistic multitasking.

Several years ago, yearbook adviser Kate Kinsella observed that staff productivity had declined due to cell phone distractions. She, along with the help of her editors, began making students put their phones in a box during class time.

Kinsella saw an immediate improvement. After instituting the same policy during Yearbook production nights, she said productivity went up.

Kinsella’s effort to fight nomophobia in the classroom is part of a larger effort to mitigate the negative effects of technology obsessions. Heisler said there are several ways to avoid the effects of nomophobia.

“Manage your electronics,” said Heisler. “Don’t let them manage you. Control how you use them versus reacting to them in the moment.”

Heisler said she recommends turning off notifications and checking phones only during designated times. She also suggested training friends not to pressure you to respond immediately and seeking in-person conversations with friends and family.

Kinsella said she tries to take a balanced approach toward students’ cell phone use in school.

“I don’t want to ban [phones] outright because I see their usefulness in both English and Yearbook,” she said. “But I also want to make sure that the environment is productive.”

Kinsella said that while not all students are enthused about putting away their phones, sometimes they appreciate it.

“Once you remove the temptation, a lot of stress associated with it is also removed,” Kinsella said.

Senior Dani Harkavy said she could become accustomed to being without her phone.

“It’s weird not being with my phone because I’m so used to it, but I think it’s like anything else,” said Harkavy. “I got used to being with my phone, so I could get used to not being with it, too.”

Malkin said that while she became used to not having her phone during eight weeks of summer camp, she eventually wanted it back.

“In the last few days of camp, you’re like, ‘I can’t wait to see my family and my phone,’” said Malkin. “When you see your parents for the first time, you ask, ‘Did you bring my phone? Is it charged?’”