All it takes is a click of a button. Just one, deliberate click and suddenly you’re not in Kansas anymore. You’re in Chile, and a war is raging on.

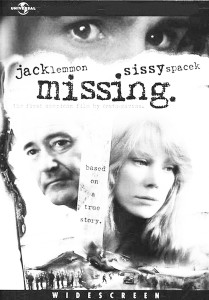

The 1982, four-time Academy Award nominee and winner of Best Adapted Screenplay, “Missing,” is director Costa-Gavras’ account of a true story and attempt at a bold political statement. This pulse-quickening drama relays lessons to which we can all connect.

Although “Missing” is considerably older than us 21st century kids, the misunderstandings shown between parent and child in this movie are ageless. Because of this, “Missing” shouldn’t be missed by the younger generation.

The movie begins with Charlie Horman (John Shea), and his wife Beth (Sissy Spacek) living in Chile to absorb its color and culture. Then a civil war breaks out, martial law is declared and one day, soldiers come and take Charlie away. The movie is an account of the struggle of Beth and her father-in-law, Ed Hormon (Jack Lemmon), to uncover the truth of what happened to their loved one.

When Ed, a conservative, Christian scientist, flies down to Chile to help Beth search for a missing Charlie, he is astounded at the life his liberal, leftist son chose to live.

Teenagers are often well acquainted with the feeling of being misunderstood by their parents. Such times seem to invariably arise when parents think they know what is best, just as Ed thought at the start of the movie. Yet, as the search for his missing son grows desperate, Ed realizes that the seemingly great continent of distance between him and Charlie isn’t quite so great. Ed learns that Charlie was, surprisingly, just like him.

A lesson can be taken from this, my friends, and the lesson is this: you can travel a million miles away from home and not move an inch. The movie is directed to show that we are tethered to our family through powerful, innate bonds.

“Missing” was indisputably created to impart some sort of grand reflection on human nature. This was a feat it accomplished, however, at the expense of a personal connection between the watcher and the characters. This creates a divide between the characters and the viewer, severing that flush of genuine emotion we should feel when Charlie’s fate is finally discovered.

But, it is not the emotion that hits at the end of the movie that makes “Missing” great, but rather the affection we develop for the characters and their plight throughout it. Gavras’ vision, while sometimes overbearing, only serves to enhance this accumulated care.

In the end, “Missing” is undoubtedly a bridge that connects young to old and past to present, in the most heart-rending of ways.