Throughout his 22 years of teaching at Glenbrook North, Spanish teacher Todd Keeler has not seen grade inflation.

“Grades have stayed pretty much consistent here at Glenbrook North,” said Keeler. “We’ve always had a real culture of students working hard, trying to do their best, trying to get the highest grades possible, and that, in my two-plus decades here, has seemed to really stay consistent.”

According to Edgar Sanchez, lead research scientist at ACT, grade inflation is defined as an increase in one’s high school GPA, either cumulative or at the subject level, without an equal or otherwise observable increase in content mastery.

Grade inflation is happening nationwide, and many students have experienced some degree of grade inflation, but some are experiencing it at different rates, Sanchez said.

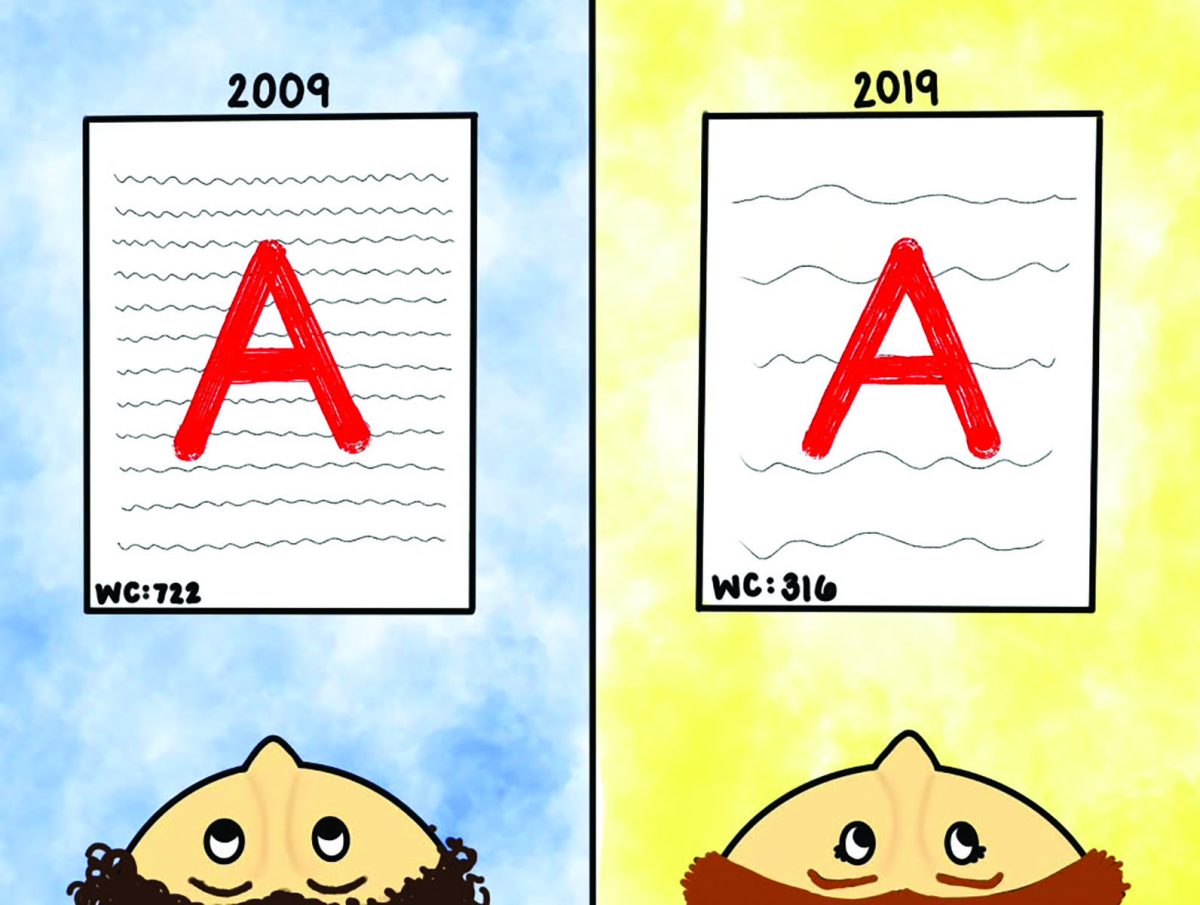

The National Center for Education Statistics, also known as NCES, gathered high school transcripts from 12th grade students in 2009 and 2019 to record their GPAs. NCES, an agency of the U.S. Department of Education, also used the National Assessment of Educational Progress, also known as the NAEP, to assess mathematics, reading and science skills.

“Twelfth grade students are doing better in 2019 than 2009 GPA-wise, but as far as the NAEP results and how these 12th graders are doing on math and reading, they’re doing worse than 12th graders were in 2009,” said Grady Wilburn, statistician at the NCES.

According to Elaine Allensworth, director of the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, attendance is down across the country, and students are reporting on surveys that both the challenge and expectations in classes have decreased.

“Test scores are down, but grades are not down,” said Allensworth. “So I think when you look at all that evidence, it does suggest that, on average, students are getting similar grades but with less challenge and engagement in school.”

“I think the real problem comes not from the grade inflation itself but from potentially having lower expectations, weaker instructional environments [and] weaker instructional practices where students are less engaged,” said Allensworth. “So if students aren’t coming to class every day … it’s going to be really hard to have that really strong instructional environment where students are continually growing, and I think that’s ultimately what’s most concerning, that then students won’t be ready for the next year.”

According to Keeler, he noticed a decrease in students’ social skills in the classroom, such as staying silent and following expectations, after the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We always want to be fair, and bearing in mind that they did lose a year, that they’re not going to get everything, that I have to reteach everything, and maybe the standard, for the time being, possibly, is not as high,” Keeler said.

According to Allensworth, to address grade inflation, the focus must be on engaging students in the classroom.

“If you have that, then the quality of instruction will be better, students will learn more and teachers will feel like their grades can be based more on how much students have learned,” said Allensworth. “They won’t feel a need to inflate grades.”

The National Center for Education Statistics, also known as NCES, gathered high school transcripts from 12th grade students in 2009 and 2019 to record their GPAs. NCES, an agency of the U.S. Department of Education, also used the National Assessment of Educational Progress, also known as the NAEP, to assess mathematics, reading and science skills.

“Twelfth grade students are doing better in 2019 than 2009 GPA-wise, but as far as the NAEP results and how these 12th graders are doing on math and reading, they’re doing worse than 12th graders were in 2009,” said Grady Wilburn, statistician at the NCES.

According to Elaine Allensworth, director of the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, attendance is down across the country, and students are reporting on surveys that both the challenge and expectations in classes have decreased.

“Test scores are down, but grades are not down,” said Allensworth. “So I think when you look at all that evidence, it does suggest that, on average, students are getting similar grades but with less challenge and engagement in school.”

“I think the real problem comes not from the grade inflation itself but from potentially having lower expectations, weaker instructional environments [and] weaker instructional practices where students are less engaged,” said Allensworth. “So if students aren’t coming to class every day … it’s going to be really hard to have that really strong instructional environment where students are continually growing, and I think that’s ultimately what’s most concerning, that then students won’t be ready for the next year.”

According to Keeler, he noticed a decrease in students’ social skills in the classroom, such as staying silent and following expectations, after the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We always want to be fair, and bearing in mind that they did lose a year, that they’re not going to get everything, that I have to reteach everything, and maybe the standard, for the time being, possibly, is not as high,” Keeler said.

According to Allensworth, to address grade inflation, the focus must be on engaging students in the classroom.

“If you have that, then the quality of instruction will be better, students will learn more and teachers will feel like their grades can be based more on how much students have learned,” said Allensworth. “They won’t feel a need to inflate grades.”